For months after Americans cast their ballots in the 1876 presidential election, no one knew with certainty who won.

The election pitted Democrat Samuel Tilden, the reform-minded governor of New York, against Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, the governor of Ohio. As the returns came in, only one thing was certain: a handful of electoral votes would determine the winner.

The New York Times boldly proclaimed Hayes the winner on Nov. 9. The New York Sun told its readers Tilden won. One day after declaring Tilden the winner on its front page, the New York Tribune threw up its hands. “Hayes Possibly Elected,” the Tribune headline read. Its lede began: “It is impossible to decide absolutely who is to be the next President of the United States,” the newspaper conceded.1

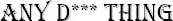

The New York Herald summed up its conclusion thusly: “NECK AND NECK; Exciting Closeness of the Presidential Struggle; WHO IS IT? The Continental Conundrum from Maine to Oregon.”2

The sharply divided electoral map of 1876 set the grass roots ablaze. “Party passion was at white heat, and consternation filled every patriotic breast,” one contemporary remembered. “The air was full of threats of violence and bloodshed, and lovers of peace and order stood appalled at the prospect.”3

Echoes of that disputed election resonated 150 years later. In 2020, President Donald Trump roused supporters with constant false claims that he had been cheated of a re-election win. Although it became clear in less than a week that Biden had won, Trump continued to assert that he was the winner. Unsubstantiated claims of fraudulent voting fueled the riotous assault on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, as Congress met to certify the election results.

Some Republicans in 1876 and early 1877 argued in favor of installing their candidate over the heated objections of Democrats, consequences be damned. They argued, just as Trump allies did in 2020, that the presiding officer of the Senate possessed the power to rule on the disputed results.

But one element differentiates the aftermath of the disputed 1876 election from the events that followed Democrat Joe Biden’s win over Trump in 2020. One of the most partisan Republicans of the Gilded Age led many of his party colleagues to support a compromise solution that forestalled the kind of mayhem that erupted at the U.S. Capitol five years ago.

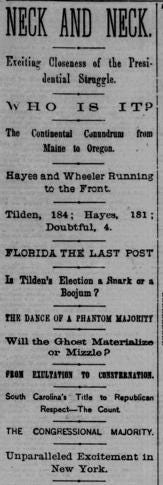

Calling Sen. Roscoe Conkling an ardent Republican would be a gross understatement. He ruled the New York Republican political machine and tolerated no dissent. He blamed Democrats for the Civil War and loathed Tammany Hall, the New York City Democratic organization that took its name from its headquarters. Conkling was especially contemptuous of reform-minded Republicans who bolted from the party and joined forces with Democrats to support Horace Greeley for president against Ulysses S. Grant in 1872 and later called for civil service reform.

Grant returned to the White House for a second term on the strength of a Republican landslide. Four years later, the Hayes-Tilden race ended in deadlock. Democrats and Republicans contested results from South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida, and disputed an electoral vote from Oregon.

With the dispute threatening to reopen the wounds of the Civil War and lead to violence, partisans from both parties braced for confrontation.

President Ulysses S. Grant reinforced Army garrisons in the South and around Washington D.C. On Jan. 8, 1877, Democratic Rep. Henry Watterson of Kentucky, publisher of the Louisville Courier-Journal, issued an ominous warning on the front page of his newspaper. While explicitly rejecting civil war as an option, Watterson urged the public to descend on Washington to overawe Congress and prevent Republicans from installing Hayes “without regard to precedents or facts.”4

When Democrats and Republicans in the House formulated a plan for an electoral commission to review the election results and make recommendations to Congress, Grant embraced the idea and asked Conkling to shepherd it through the Senate. One account of Conkling’s meeting with Grant indicates that the senator was hesitant but acquiesced. “[I]f you wish the commission to be carried, I can do it,” Conkling assured Grant.5

An unusual combination of factors enabled Conkling to act as a persuasive advocate for the commission. His standing in the party lent credibility to the proposal. He had good reason to be skeptical of Hayes, who vowed to eliminate political patronage from government hiring — the basis of Conkling’s political power. Conkling’s partisan reputation and qualms about Hayes made him uniquely suited to act as a disinterested advocate of compromise.

Conkling played an active role as congressional committees, meeting behind closed doors, hammered out the details of the electoral commission bill.6 In the end, lawmakers proposed a 15-member panel, consisting of five members from the House, five from the Senate, and five from the Supreme Court, to review disputed returns. The commission would make its recommendation, and both houses of Congress would vote on it. Its recommendations would become final if one house accepted them.

With Democrats holding a majority in the House and Republicans a majority in the Senate, this plan — at least on paper — seemed designed to achieve a partisan balance.

But some Republicans considered it unnecessary. Like Trump supporters in 2021, Republican Rep. James A. Garfield of Ohio believed the presiding officer of the Senate possessed the power to rule on the validity of returns, and he shrugged off the prospect of violence. “A little bluster, a new burst of newspaper wrath, and all would have been over,” Garfield wrote to Hayes. “A compromise like this is singularly attractive to that class of men who think that the truth is always halfway between God and the devil, and that not to split the difference would be partisanship.”7

Conkling disagreed. In two speeches delivered over the course of two days, he delivered a tour-of-the-horizon defense of the electoral commission.

He began with a lengthy critique of the argument that the president of the Senate could count the returns. In 2021, Trump’s team asserted that Vice President Mike Pence — as the Senate’s presiding officer — was the “ultimate arbiter” who could rule on the validity of electoral votes. In 1877, Conkling argued that a careful parsing of the Constitution distinguishes between the opening of electoral certificates and tabulating them. Article 2, Section 1 assigns only the first task to the Senate’s presiding officer, he told his colleagues.8

The following day, Conkling addressed the political arguments in favor of the commission. He warned that relying on the Senate’s presiding officer to arbitrarily install Hayes in the White House — the plan advocated by Garfield and Sen. Oliver Morton, R-Ind. — threatened to open a “political Hell-Gate paved and honeycombed with dynamite.”

Speaking to his Republican colleagues, Conkling appealed to their devotion to the Constitution. “I say it is not for the representatives of a patriotic party of law and order, in the presence of the events before which we stand, to refuse by law to constitute a peaceful, certain, impartial under the Constitution, and above it, of ascertaining the true result of the recent election.”9

The effectiveness of Conkling’s advocacy became clear when the Senate voted 47-17 for passage of the commission bill. Only 16 of the Senate’s 46 Republicans voted against. The Nation, a liberal organ often hostile to Conkling, grudgingly conceded his speech was a “great success.”10

The same could not be said for the commission. On a series of 8-7 votes, the panel sided with Republican claims in each of the three Southern states and Oregon. Democrats groused and dubbed Hayes “His Fraudulency,” but the rulings enabled the Ohioan to take office in March.

During his years in the Senate, Conkling was not known as a legislator. But passage of the electoral commission bill was an undeniable triumph. It resolved, albeit imperfectly, the disputed election. Violence was averted, and the peaceful transfer of power protected.

At Conkling’s death in 1888, New York Democrat Abram Hewitt credited him with acting to avert civil war. “He loved his party,” Hewitt remembered, “but he loved his country first.”11

“THE BATTLE WON,” New York Times, Nov. 9, 1876, p. 1; “THE PRESIDENT ELECT; Samuel J. Tilden Elected President of the United States,” New York Sun, Nov. 8, 1876; “TILDEN ELECTED,” New York Tribune, Nov. 8, 1876, p. 1; “HAYES POSSIBLY ELECTED,” New York Tribune, Nov. 9, 1876, p. 1.

“NECK AND NECK,” New York Herald, Nov. 9, 1876, p. 3.

Milton Harlow Northrup, “A Grave Crisis in American History: The Inner History of the Origin and Formation of the Electoral Commission of 1877,” The Century Illustrated Vol 62, May-October 1901, p. 923. Hereafter cited as Northrup.

Henry Watterson, “The Political Situation,” Louisville Courier-Journal, Jan. 8, 1877, p. 1.

Albert M. Gibson, “A Political Crime: The History of the Great Fraud (New York: William S. Gottsberger, Publisher, 1885), p. 29.

Northrup, pp. 928, 930-932.

James A. Garfield to Rutherford B. Hayes in Charles Richard Williams, Diary and Letters of Rutherford B. Hayes, Vol. 3 (The Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society, 1924), pp. 408-409).

“Final Report of the Select Committee to Investigate the Jan. 6 Attack on the U.S. Capitol,” in The Jan. 6 Report (New York, Twelve Hatchette Book Group, 2002), p. 362; U.S. Congress, Senate, Congressional Record, 44th Congress, Second Session, Vol. 5, Jan. 23, 1877, p. 826.

Ibid., U.S. Congress, Senate, Congressional Record, 44th Congress, Second Session, Vol. 5, p. 826.

Ibid., Jan. 24, 1877, p. 912; “The Debate on the Settlement,” The Nation, Vol. 24-25, Feb. 1, 1877, p. 71.

“Four Views of Conkling,” Washington Post, April 20, 1888, p. 4.